Beyond the Gold Standard: Understanding the Pitfalls of Forensic DNA Evidence

Beyond the Gold Standard: Understanding the Pitfalls of Forensic DNA Evidence

DNA: Powerful but not perfect

It all begins with a trace. A drop of blood, saliva on a cup, or hair on a jacket. These tiny fragments of life have transformed modern justice, as they each contain DNA. For more than three decades, DNA has solved cold cases once thought unsolvable, freed the wrongly convicted, and secured guilty verdicts (National Research Council, 1996). In our criminal justice system, DNA has become a symbol of scientific certainty, even more so as the “gold standard” in forensic evidence.

DNA is found in all living things, including us. It carries our genetic code and determines all our biological any traits, including visible features like hair and eye colour. In fact, DNA is so unique that even identical twins differ in subtle ways. With that kind of individually written into our cells, it is easy to see why DNA evidence feels infallible. Yet that belief is misleading as the reality is much more complicated. Here lies the paradox: DNA is powerful, yet it is never absolute.

DNA isn’t magic, it’s science, and science always has limits. In recent years, forensic scientists have shifted away from the language of “matches” toward probabilities. This reasoning stems from the work of Thomas Bayes, whose ideas form the foundation of Bayesian reasoning (Aitken et al., 2024). Rather than proving guilt in absolute terms, Bayesian reasoning helps scientists express how likely one explanation is compared to another. Evidence doesn’t establish truth but updates our understanding of how probable a scenario is, given the available evidence.

What actually happens in the laboratory

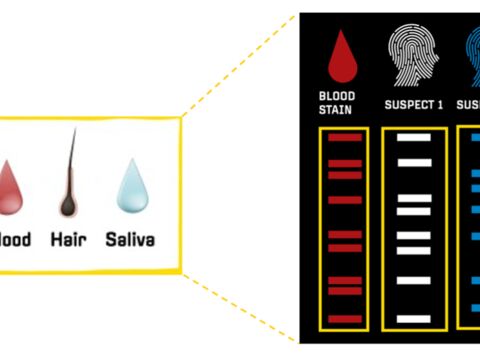

In the laboratory, DNA is recovered from blood, saliva, semen, hair, or even skin cells shed from everyday contact (see image below). These traces are collected at crime scenes, analysed and compared to known samples in a database. When a profile matches a suspect, it’s often described as a match (can you match the suspect to the bloodstain in the figure below?). Contrary to what TV dramas suggest, forensic scientists don’t read your entire genetic code. That would be far too expensive, time consuming, and unnecessary.

Although 99.9% of our genomes are identical across all humans, small regions vary in ways that make us distinguishable. DNA fingerprinting uses these variations to identify individuals (Sarah Sharman, 2021). It focuses on specific regions known as Short Tandem Repeats (STRs) (Nwawuba Stanley et al., 2020). These STRs are small pieces of DNA that are particularly varaible between people.

By comparing patterns across a set of STR markers, forensic scientists create a kind of genetic fingerprint. The odds of two unrelated people sharing the same profile at all these markers are so astronomically low — sometimes as rare as one in 180 billion— that it gives the feeling of certainty. Yet, those odds are still probabilities. For example, this statistic assumes ideal conditions. In reality things are rarely so simple. DNA can degrade over time, mix with DNA from other people, or be transferred elsewhere indirectly. Each of these factors increases uncertainty. That’s why forensic experts now rely on probabilistic models to account for these errors,with a new movement stressing the use of probabilities in the form of likelihood ratios.

The match myth

Because of these uncertainties, forensic scientists avoid statements such as “it’s a match”. Instead, they calculate what is called a likelihood ratio. This ratio compares two competing scenarios:

- DNA came from the suspect

- DNA came from someone else

If the ratio heavily favours the first scenario, the evidence sounds persuasive, especially when the numbers stretch into the billions. But this is where trouble begins. Lawyers, jurors, and even judges sometimes misinterpret the number as the probability of guilt, this is what we call the 'prosecutor’s fallacy'. This is an error that turns the numerical value into a guilty conclusion. You might be thinking what the heck, but let us break it down. The logic usually goes: imagine a DNA profile is so rare that only 1 in a billion people might have it. A lawyer might then argue “that means there’s only a 1 in a billion chance the DNA belongs to anyone other than the defendant, so it much be them”. Sounds convincing, right? But it’s wrong. This statistic only tells us how rare the profile is in the general population. It does not tell us the chance the suspect is guilty.

Alternatively, think of it like this, if you play the lottery, your odds of winning are tiny, say 1 in a billion. If someone wins, we can’t say they were destined to win. It just means that someone had to, and it turned out to be them. The same logic applies in DNA. Therefore, this fallacy confuses the rarity of your DNA profile with the probability of guilt.

This is where Bayes’ theorem becomes essential. In Bayesian reasoning, scientists are able to combine the likelihood ratio with prior information, for instance, the context of the crime, to update the probability of a scenario. For example, as a way to explain other plausible ways why a person of interest's DNA was found at a crime scene. It’s a structured way of saying “given what we already know, and this new DNA evidence, how much should our confidence in the DNA evidence match charge?”.

This is where context matters

Even when we know whose DNA was found, that doesn’t necessarily tell us how(!) it got there. This is where things can get way, way more complicated. In the previous section we looked at some sources of DNA. But before a person is a suspect, we need context, we need to create more scenarios on the activities that led to DNA being deposited and how that influences our drawn-up probabilities. This is where it can become so complicated, that this is still being tested in our legal systems in what we call 'activity level' analysis (Netherlands Forensic Institute, 2023).

Let us take the case of Lukis Anderson in California (Worth, 2018). His DNA was found under a murder victim’s fingernails. The statistics looked damning, but Anderson had been in hospital, unconscious on the night of the crime. The truth was that paramedics had unknowingly transferred his DNA from the hospital to the crime scene while treating both men (Worth, 2018). Without considering this activity-level context, Anderson’s DNA appeared to prove guilt. With context, the probabilities were in favour of innocence.

Forensic scientists now build activity-level models to test multiple plausible scenarios dealing with questions such as: 'was the DNA transferred directly or indirectly?' Or, 'How long could it have persisted?' Bayesian networks help weigh these probabilities, combining science, logic and judgement. It is a powerful reminder that DNA evidence doesn’t speak for itself, but we humans need to interpret it (Netherlands Forensic Institute, 2023).

Takeaway: DNA as a double-edged sword

Popular culture and shows like CSI, Bones, and NCIS have shaped public belief that DNA delivers instant, definitive truth. In reality, analysis takes time, samples are often partial or degraded, and results must be interpreted with layers of probability, such as the activity level analysis.

Hopefully this article brought some clarity on how DNA evidence really works. DNA evidence is extraordinary, changing the course of justice more than any other forensic tool in history. Just a simple internet search shows the rapid developments that occur in terms of technologies and reasoning on the interpretation of evidence. Yet, take caution and really think about what the DNA evidence is telling you. Therefore, the next time you hear a lawyer declare that DNA proves guilt “beyond doubt”, remember science doesn’t deal with absolutes.

So, the final answer: friend or foe? The answer is both. It can exonerate or implicate, clarify or confuse. What matters most is not the glitter of the “gold standard”, but how we choose to interpret it.

This article was written by Frankie Gloerfelt-Tarp, a Science Communication student.

Sources

Aitken, C., Taroni, F., & Bozza, S. (2024). The role of the Bayes factor in the evaluation of evidence. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application, 11(1), 203-226.

National Research Council (US) Committee on DNA Forensic Science: An Update. The Evaluation of Forensic DNA Evidence. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1996. 6, DNA Evidence in the Legal System. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232607/

Netherlands Forensic Institute, An activity-level evaluation by a forensic expert (V1), June 2023.

Nwawuba Stanley U, Mohammed Khadija A, Bukola AT, Omusi Precious I, Ayevbuomwan Davidson E. Forensic DNA Profiling: Autosomal Short Tandem Repeat as a Prominent Marker in Crime Investigation. Malays J Med Sci. 2020 Jul;27(4):22-35. doi: 10.21315/mjms2020.27.4.3. Epub 2020 Aug 19. PMID: 32863743; PMCID: PMC7444828.

Sharman, S., (2021, November, 11). An Everyday DNA blog article, HudsonAlpha, https://www.hudsonalpha.org/forensics-and-dna-how-genetics-can-help-solve-crimes/

Worth, K., (2018, April, 19). Framed for Murder By His Own DNA, The Marshall Project, https://www.themarshallproject.org/2018/04/19/framed-for-murder-by-his-own-dna