The Inevitable Fate of the Queen Conch

The Inevitable Fate of the Queen Conch

The Caribbean’s treasure

The queen conch (Aliger gigas) is a marine sea snail that is found throughout the Caribbean and the Florida Keys. In this region, the queen conch is more than just a sea snail: it’s both a livelihood and a symbol of cultural identity. The species has been a delicacy for centuries and is both popular among inhabitants and tourists. After the spiny lobster, the queen conch is the Caribbean’s biggest seafood moneymaker. It brings in an estimated value of 74 million USD across the Caribbean.

With Caribbean holidays growing in popularity, the queen conch is paying the price. Decades of unsustainable harvesting, combined with the queen conch’s slow movement and late sexual maturity, has resulted in a population crash. In 1992, this led to them being listed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, better known as the CITES list.

Different rules, different fates

Since being a protected species, many Caribbean countries have local regulations to manage and conserve queen conch populations. These range from minimum size and weight requirements to seasonal harvesting closures during the reproduction period and outright harvest bans. The level of protection and how strictly it is enforced varies between the individual countries in the Caribbean.

This leads to stark contrasts in population sizes: on some islands, outright bans are helping the queen conch to bounce back, while just tens of kilometres away, weak enforcement on another island is threatening populations towards extinction. A rather extreme example of this is the island Sint Maarten, an island of just 88 square kilometres, that is split in a Dutch side and a French side, each with their own set of rules. With stricter regulations enforced on the French side, fishermen from both sides turn to the Dutch waters to harvest queen conch, putting the population under immense pressure.

Outdated regulations

As if being targeted by twice the usual fishing pressure weren’t bad enough, the Dutch side’s inadequate regulations are leaving the queen conch even more vulnerable. The only regulations that are enforced are a minimum shell size of 18 centimetres and having a permit. To make matters worse, the authorities often turn a blind eye to the latter. The former is based on outdated information that was meant to determine the life stage of an individual. The idea is that individuals who are at least 18 centimetres in shell length are sexually mature and have had the chance to reproduce and thereby ensure future populations.

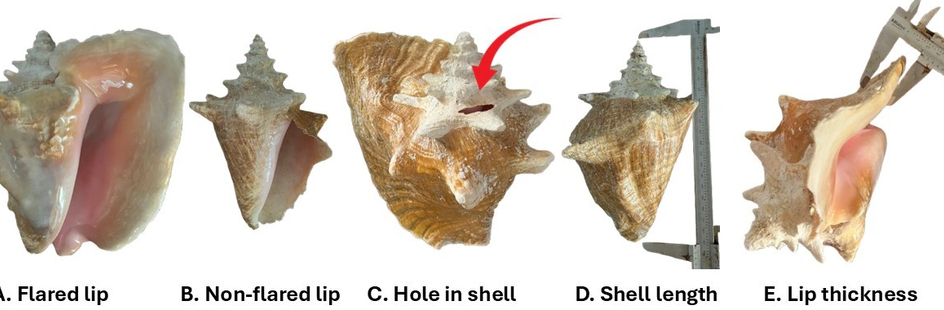

However, this information is an unreliable indicator and thereby directly contributes to the ongoing depletion of the population. During the juvenile stage, the conch primarily grows by increasing their shell length, but they already reach their maximum shell length before they are sexually mature. Only after they have started reproducing, the edge of their shell flares outward to form a so-called ‘lip’. This lip starts thickening once the conch has reproduced for the first time, providing a much better indicator of maturity than simply measuring shell length.

The maturity measure

We now know that the lip thickness reveals sexually maturity, but only exact measurements can make protection effective. Scientists studied this by collecting 200 queen conches during the peak breeding season in Belize. They measured the lip thickness of each individual and then performed microscopic examinations of the gonads (sexual organs) to check for sexual maturity. By matching each individual’s lip thickness to whether or not they were capable of reproduction, they estimated the lip thickness at which 50% of queen conchs were sexually mature. This threshold was found to be 15.51 mm for females and 12.33 mm for males.

Conch in crisis

As long as regulations focus on shell length instead of lip thickness, the queen conch is headed for an inevitable fate: extinction. This is already happening in the Dutch waters around Sint Maarten, where an alarming number of 14.78 adults per hectare have been found. By comparison, an ideal number of 200 adult conch per hectare are needed to achieve maximum reproduction rates, and below 50 adults per hectare, reproduction is practically absent.

Extinction of the queen conch would have serious ecological consequences. As herbivores, they prevent algae from overgrowing, thereby helping to maintain healthy seagrass beds. These play an important role in carbon storage, water quality, and a nursery for marine species. On top of that, Sint Maarten’s economy relies on the queen conch as the second highest seafood moneymaker, and a piece of national heritage would be lost without the conch being part of the Caribbean cuisine.

Turning the tide

These consequences should lead to the logical choice that current regulations should be revised. Experts are calling for a minimum lip thickness requirement of 16 mm, ensuring a high chance that only fully mature conch, that have had the chance to reproduce and secure future populations, would be harvested. This would lead to more sustainable harvesting, allowing conch to recover their depleted population levels. Healthier populations mean more queen conch in the long term, supporting local fisheries, restaurants, and tourism. So even though the rulebook has fallen short, we have the power to replace it with science-based protections, giving the queen conch a chance to rewrite their fate that once seemed inevitable.

This article was written by Sterre de Bruin.